I just finished reading “Potlikker Papers, A Food History of the Modern South” by John Edge. I have spent many years exploring my own personal food history and that of my family’s and the region we live in. Our history is chronicled through the food that we grow, cook and eat. The narrative is shaped from the kitchen stove and from the dining room table where we convene as families, friends and communities to do much more than fill our stomachs. These food memories and traditions are played out throughout the holidays as we cook and eat foods that our families have been serving for decades to celebrate our heritage and time together.

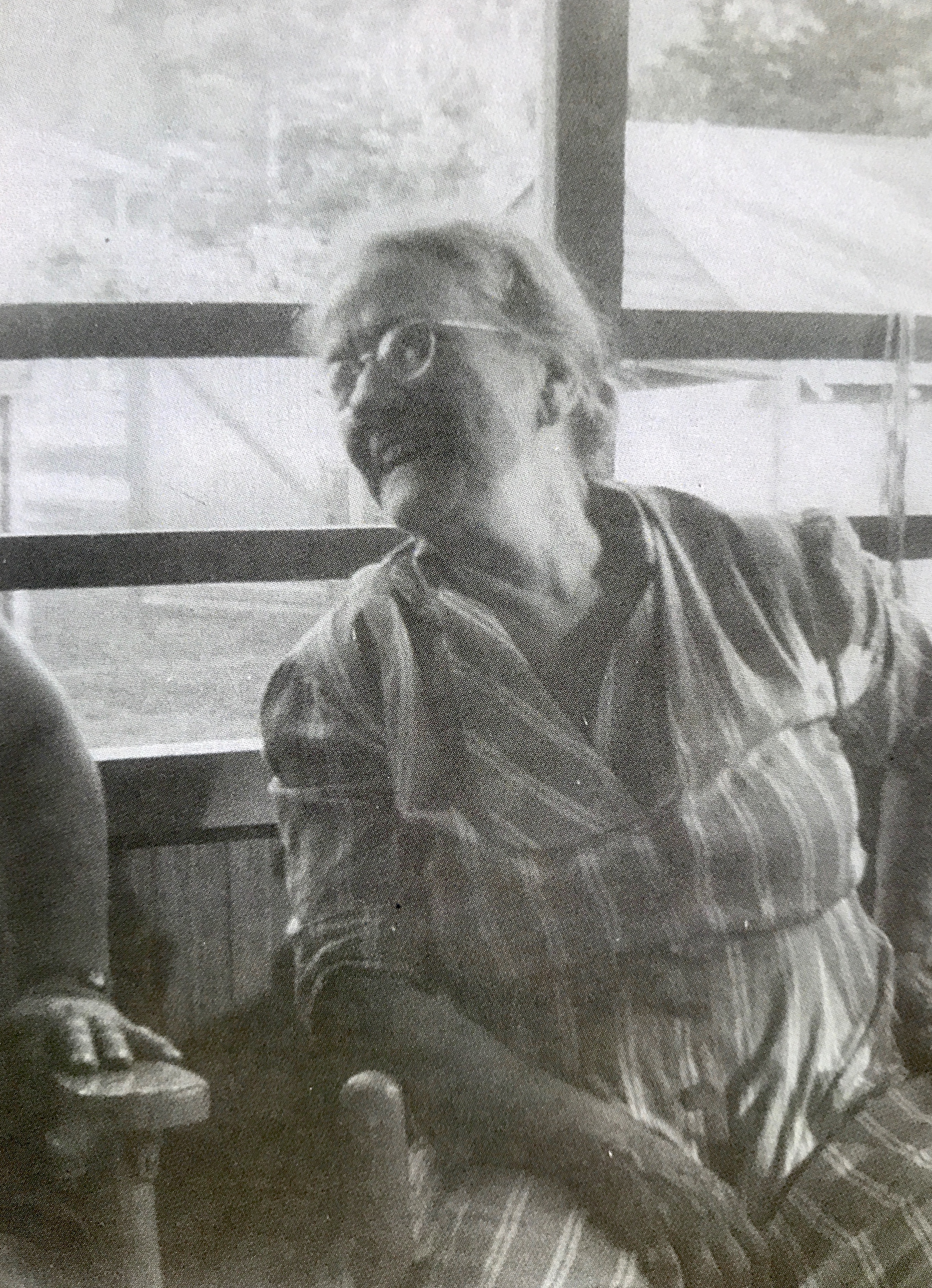

My great grandmother Lucille Bernard Cocke

I descended from a long line of fine Creole cooks. Lucille Bernard Cocke, my great grandmother and mother of Gladys Cocke Toca, “Maw Maw,” my paternal grandmother, who was known as “Sweet Lu” by many. Her husband, Clarence Cocke, lovingly referred to her as “wife.” To the rest of us she was and always will be known as “Granny.”

Lucille Bernard was born on September 1, 1875 on St. Delphine Plantation in West Baton Rouge near Addis. Her father, Henry Clay Bernard, and her grandfather, Leon Bernard, were sugar cane farmers from Lafourche Parish. She died in 1954 the year after I was born, so I do not have any memory of her. Her memory lives on, however, through the tradition of passed down recipes that are still prepared today by my mom, aunts and cousins, and me and my daughter, Maggie. My dad, Melvin Toca, barely recollects ever seeing Granny leave her station at the stove in the kitchen. He waxes eloquently on the endless pots of savory seafood gumbo and the all you could eat perfectly formed thin crepes hot off the griddle. No one could quite cook a crepe or a gumbo like Granny. The family slogan has always been, “that’s good, but not as good as Granny’s.”

Cocke’s Roost, Granny’s summer home in Clermont Harbor on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, was overrun with my immediate family and our many cousins and friends during the summer months. It was a child’s paradise filled with joyful bliss and freedom. Fond food memories of fresh boiled crabs caught that morning from the pier, or fried croaker from Bayou Caddy served with grits for breakfast, still have a place in my heart. Popee, Sidney Toca, my grandfather, always needed help from the grandchildren or “cochons,” as he fondly referred to us, cranking the ice cream maker to produce his unforgettable Creole cream cheese ice cream. We each held a position and place of importance in the creation of our family food history.

Maw Maw, Sidney’s wife and my grandmother, was renowned for her creole lunches. It was not unusual for Maw Maw to spend the day in the kitchen roasting veal, stewing beef grillades, simmering a well-seasoned black iron pot of jambalaya, preparing a red bean puree or baking a pineapple upside down cake. Maw Maw taught me the art of elevating a common lunch to haute cuisine.

I grew up learning all of these recipes and rituals in the kitchens of my mother, grandmothers, aunts and family friends. As John Edge stated in “Potlikker Papers,” we have a “shared culinary language,” not only with our southern families but across the country. Food traditions such as mine from my family and others from the south have been shared, fused and assimilated into a new, fresh American cuisine which pays homage to our ancestors, and the immigrants to our region creating and resulting in the rich food history and culture we enjoy each day.

I plan to re-explore many of these family food traditions and recipes throughout Thanksgiving and the holiday season. I can’t wait to share our family recipes with you for our shrimp stuffed mirlitons, smoked turkey and sausage gumbo, baked oysters, sweet potatoes, and more. I may even share a few of our retro recipes and family favorites for olive surprises and daube glace. I hope that you will join me this holiday season in creating your own culinary reminiscences!

Comments are closed.